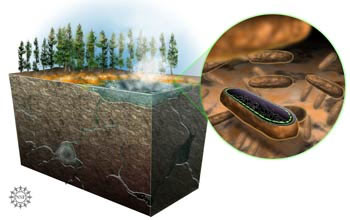

Researchers looking at bacterial mats in Yellowstone’s thermal pools discovered a strange new species that uses chlorophyll to convert the sun’s energy into chemical energy.

Scientists found the bacteria, called Candidatus Chloracidobacterium thermophilum, in Octopus and Mushroom springs and the Green Finger Pool, not far from Old Faithful. The bacterium grows best in temperatures between 120 and 150 degrees Fahrenheit and could help researchers drastically increase production of biofuels, according to Don Bryant, a professor of biotechnology, biochemistry and molecular biology at Penn State University.

Bryant said it’s rare to find new micro-organisms that are using light energy. Since 1906, scientists have found only three bacteria that show similar capabilities. Further, Chloracidobacterium thermophilum is the first photosynthetic member of a newly discovered group of bacteria called acidobacterium.

Bryant found the bacterium by looking at DNA information gathered by David Ward, a researcher with Montana State University who has spent decades investigating Yellowstone’s bacterial mats. Bryant said he looked through hundreds of DNA sequences on a computer screen to find the new species.

“We’re looking for signatures of genes that are distinctly different than anything that’s known,” he said.

What Bryant found was a DNA sequence that was closely related to DNA in a bacteria called cyanobacteria. Next, Bryant had to prove the bacteria actually existed.

“A virtual organism, something that we had found only on a computer, is not something that can be publishable in Science,” he said. “Most of the next year went in to trying to isolate the organism, finding out what properties it had, and demonstrating that it actually can convert light energy into chemical energy. It’s not whether you’ve got some genes, it’s how you’re using them.”

Normally, a researcher might grow a group of bacteria on a plate and then by hand separate out the individual bacterium he or she is interested in. Unfortunately, Chloracidobacterium termophilum grows in 130-degree water that is slightly alkaline, making it extremely hard to get a pure culture.

Instead, Bryant started with a group of three bacteria, subjecting study groups to light and dark conditions to find out how well they grew. Eventually, Bryant killed off one bacteria with an herbicide, ruled out another microbe that doesn’t use light to grow, and successfully isolated Chloracidobacterium thermophilum.

“We got the proof that the organism that was growing on light energy,” he said. “We grew the organism repeatedly in light and dark. If you grow it in the dark, it grows much more slowly, if at all. If you grow it in light, it grows much faster.

Chloracidobacterium thermophilum is similar in appearance to E. coli, a rod-shaped single-cell organism two microns in length by three-fourths of a micron in diameter. A micron is 1/1000th the size of the diameter of a piece of lead in a mechanical pencil. The organism or organisms that are very closely related are likely found in hot springs around the world, traveling on the feet of birds as they migrate.

Since his initial discovery, Bryant has gathered evidence that suggests Chloracidobacterium thermophilum is aerobic, or breathes oxygen (another anomaly for a photosynthetic bacteria), and doesn’t take carbon from the atmosphere to increase its cell size and reproduce. Instead, Chloracidobacterium thermophilum likely gets its carbon from the waste of other bacteria.

By removing waste products, Chloracidobacterium thermophilum probably helps other bacteria grow much faster, a prospect that could lead to practical applications. Scientists are currently growing bacterial mats that they ferment to make ethanol. A bacteria that could double the production of biomass for ethanol production could be commercially valuable, Bryant said.

“If you’ve got a system that captures twice as much light energy, then you’re a lot better off,” he said. “We don’t think the Department of Energy [and other organizations] have spent enough time thinking about this. It’s really not all that complicated to get a little more bang for your buck.”